Improving the on-scene communication connection

By Scott R. Connor

Chief of Training, TEAM-1 Academy Inc.

Over the last 30 years of my career cleaning up hundreds of hazmat incidents and completing thousands of trainings, I've found the number one issue that either causes a hiccup during the operation or sends it completely sideways is communication.

There are so many aspects and levels of communication that it is no wonder why this can become an issue. As a responder in a chemical suit, here are some of my tips on how to increase your success within the operations sector:

1. Don't purchase or use a communication system for the entry teams if it is too complicated or if you haven't practiced enough to become proficient. Communication at the best of times is tough in a Level A suit, but purchasing a state-of-the-art communication system for the entry teams only works if everyone knows how to use it, including the staff assisting in suiting up and the officers giving instructions.

I have seen several occasions in which much of the mobility/set-up has been focused on trying to sort out the entry team's communication system (i.e., how it attaches to the ear or throat, where the wires go, attachment to the radios, radio checks, volume issues, voice activation issues, and the list goes on). If crews are not able to put in the training to overcome all of these issues, then you may as well just hang a radio with a remote mic inside the suit since all the crews know how to run that set-up.

2. Only give the entry team three to four tasks to accomplish during their entry. I always want to know what my team is doing while in the hot zone, so I have found that limiting their tasks to three to four items to accomplish has worked very well. It is hard to remember too many tasks in high stress situations. In addition, I have them accomplish their tasks in a particular order. After each task is completed, I require that they transmit so that I can track time and so that I can keep Incident Command updated.

3. Don't give instructions while the responders are zipped up and on air. So many times, I see the entry team receiving commands while they're zipped up and on air in the cold zone. There are a few reasons to avoid this. First, the air in the cold zone is safe to breathe; it is best to save breathing cylinder air until it is needed. Second, when the entry team is zipped up and on air, their adrenaline is pumping and the sound of pneumatics, alarms or beeps are amplified inside the suit. This means that when they receive commands, they are likely only half listening. I have way more success when I have them dressed up, but with the mask off their face to receive information. This also allows them to ask questions should any clarification be needed.

4. Decide ahead of time who will be the main communicator in the suits. Imagine we are on a push-to-talk (PTT) system of radio communication for this example. If both responders start hitting their radio PTT every time there is a request, then it really slows down hot zone production. Before they are zipped up and on air, decide who will be in charge of the radio, flashlight and gas detector. This leaves the second responder fairly hands free to get the tasks completed much more quickly, since they are not both searching for radios every time there is a broadcast or an update is required.

5. If you must keep asking the entry team to repeat themselves after every transmission, try to address this during training. Sometimes even with sufficient training, this does pop up from time to time. This can be a radio problem, but it is often an issue with the location of the microphone within the suit. Don't be afraid to ask the entry team member communicating to move the radio to a new location until it improves. In the worst-case scenario, I will have the entry team members change roles and have the other person become the main communicator.

6. Always debrief after an entry before sending in the next entry team. It is surprising to find out during a debriefing that a task you were sure they said was completed is not or that a description of a situation is entirely the opposite. I have seen many entry teams being sent in just as the prior entry team is stepping out of Decon to find out they need to radio the entry team in haste to change their tasks. Take a few minutes to debrief with the first entry team and confirm everything, so that the next entry team can complete their entry in the least amount of time.

I want my entry teams to spend the least amount of time in the hot zone. Spending extra time thinking, planning and communicating in the cold zone will result in quicker in and out times for your entry teams.

Decoding NFPA standards for chemical protective clothing

By Susan Lovasic (ret.)

Global Regulatory Affairs Manager, DuPont Personal Protection

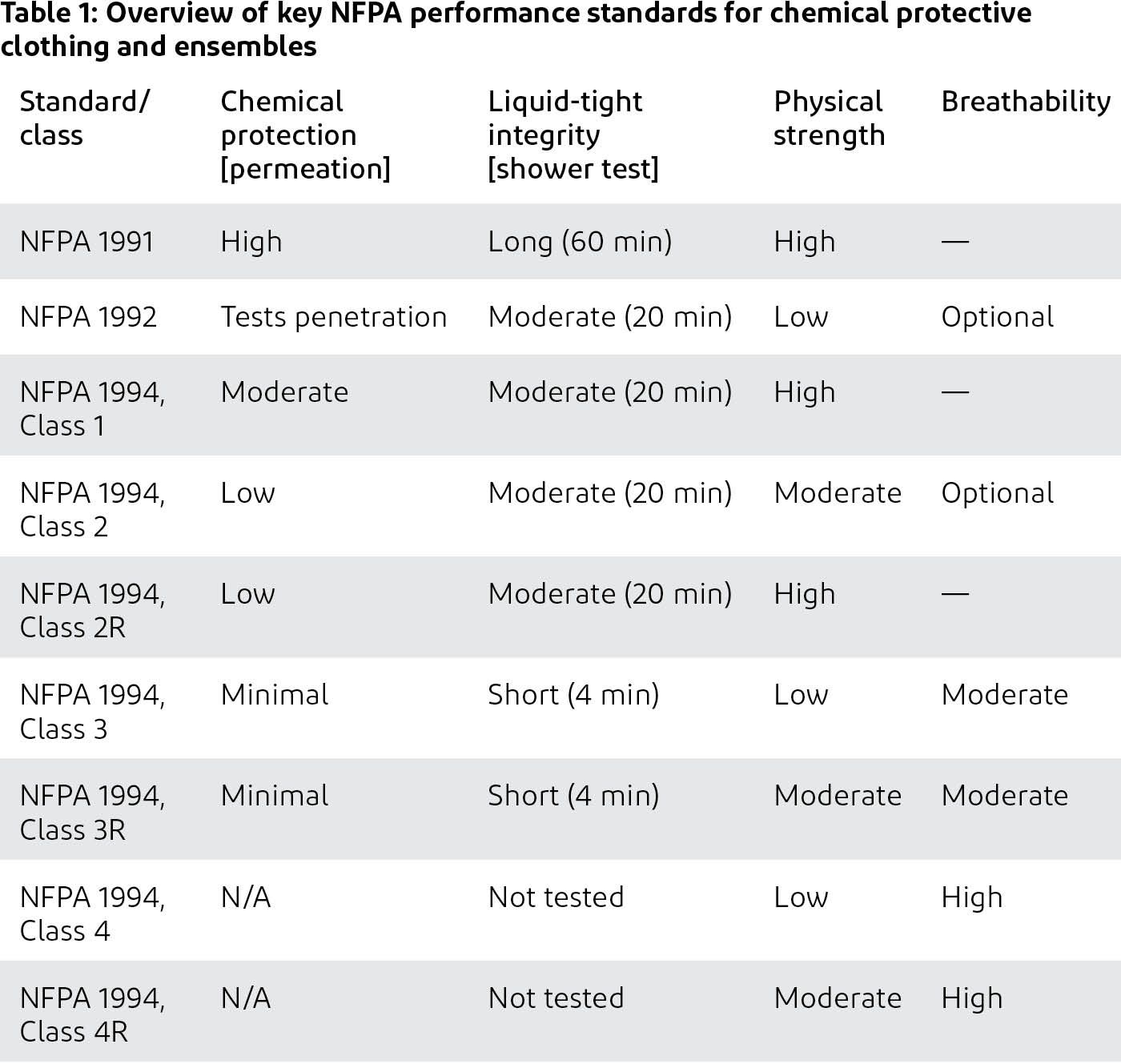

For chemical protective clothing (CPC) used in the US, several key certification standards are published by the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA). There are currently three main NFPA standards covering hazmat PPE. These standards are NFPA 1991, 1992 and 1994. NFPA 1994 offers seven unique classes within the standard, so there are a total of nine possible varieties of NFPA-certified suits for hazmat PPE. The "R" designation after NFPA 1994 Classes 2, 3 and 4 is used to denote a "ruggedized" version of each; they have higher physical strength requirements, but use the same chemical barrier requirements as the non-ruggedized versions. This article will highlight key differences to help determine whether a garment certified to a particular NFPA hazmat standard will offer the appropriate level of protection for the chemical hazards identified in your assessment.

Each NFPA hazmat clothing standard covers a different scope or purpose and therefore uses different tests and requirements. When deciding whether a CPC item certified to an NFPA standard is appropriate for your chemical exposure, it is helpful to understand how certified suits were evaluated. Table 1 below provides a high-level overview of the nine options available from NFPA 1991, 1992 and 1994 standards, along with some key performance levels.

While many of the same tests are used in these NFPA standards, the performance limits vary significantly because of the different scopes and expected performance levels of the suits. For example, all but two of the options require a "shower test" to evaluate liquid tight integrity of the suit/ensemble. But as noted in Table 1, the length of exposure to the shower test varies from 60 minutes to just 4 minutes. This is not surprising since the scope and/or application for these standards are different.

Decisions regarding CPC selection will directly impact the health and safety of workers. When selecting CPC, the greater your knowledge of different types of suits available (whether certified or not) and how they were evaluated will improve your ability to find the best match to protect from the chemical hazards of concern. CPC that is certified to an NFPA hazmat standard can offer benefits if the certification requirements match the protection needs identified in your hazard assessment.

Please note that NFPA standard performance levels discussed in this article are the minimum requirements. Nothing in any of these NFPA standards restricts the manufacturer from exceeding these minimum requirements. Therefore, if performance requirements of a suit certified to an NFPA standard do not match your hazard protection needs, further information may be requested from the suit manufacturer to determine whether any additional relevant testing was performed above what NFPA required.

This article is an excerpt from Occupational Health & Safety. If you'd like to learn more details regarding these NFPA hazmat standards and CPC selection, the full version of this article originally appeared in the July/August 2019 issue.

Tychem® 10000 – The original Glow Worm suit with new enhancements

By Catherine Brear

End Use Marketing Manager, DuPont Personal Protection

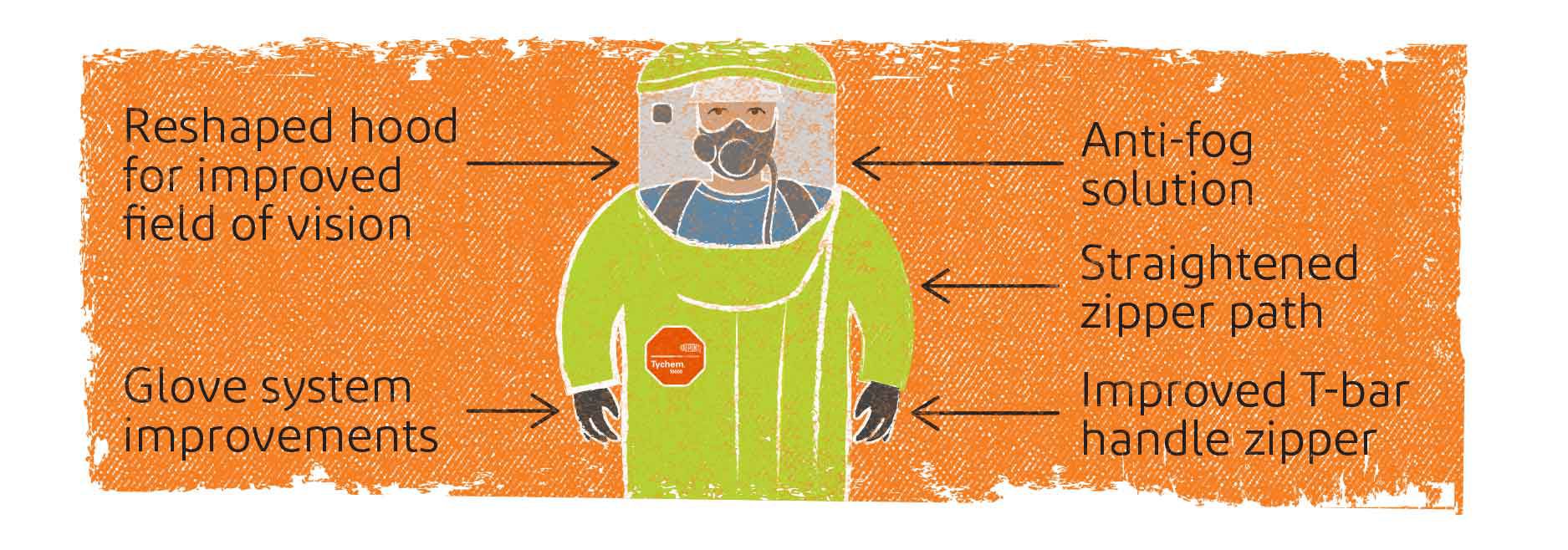

If you've used Tychem® 10000 Level A suits in the past and recently ordered new ones, you may have noticed some changes. DuPont uses voice of customer input to develop new products and to improve and enhance existing garments. Recent customer feedback has led DuPont to make a number of significant design improvements to Tychem® 10000 suits to better meet your needs.

Improvements we've made include:

- adopted a more flexible, T-bar handle zipper for easier donning and doffing

- implemented glove system improvements to prevent glove inversion

- added an anti-fog solution to each encapsulated suit visor

- reshaped the hood for improved overall field of vision and downward visibility

- straightened the zipper path to reduce the likelihood of kinking

Hazmat through history – bleach

By Catherine Brear

End Use Marketing Manager, DuPont Personal Protection

Given recent events, there has been a renewed focus on cleaning and disinfecting households and workplace facilities alike. So, we wondered, when was bleach first discovered and how did bleach solutions come to be used as disinfectants?

Liquid bleach has a variety of uses, but for many of us, we associate it with trying to remove a tough stain from a white shirt. Initially, according to Britannica, "sunlight was the chief bleaching agent up to the discovery of chlorine in 1774" by Carl Wilhelm Scheele. The discovery of chlorine and the understanding of its properties shifted the landscape; bleaching processes that might have previously taken months in the sun could now be completed in hours.

Chlorine bleach (i.e., sodium hypochlorite) is a common disinfectant used in households and facilities today. According to How Stuff Works, bleach was first used as a medical disinfectant at a hospital maternity ward in Vienna, Austria, in 1847. There, workers used chlorine bleach to help prevent the spread of what they called "childbed fever," or postpartum infections that killed many women after childbirth. In the United States, chlorine bleach was not heavily used until the 20th century due to its high cost to manufacture.

As with many common household chemicals, it's always important to ensure you are wearing the proper protection when cleaning and disinfecting surfaces, especially since chemicals like bleach can be hazardous if they are not used properly. Stay safe and happy cleaning.

Products and/or sales questions?

Share your stories, tips and tricks.

Resource library

Find technical information, videos, webinars and case studies about DuPont PPE here.